Post G-20 Summit Update

As an update to our recent piece on the China/U.S. trade war we wanted to provide a brief update on the events that have transpired since. The G20 meeting in Tokyo in June included a meeting of Presidents Xi and Trump where they hit the reset button on trade negotiations between the U.S. and China after discussions derailed in May. Much of what was reported as coming out of the meeting may be speculative and/or subject to change. Nonetheless, President Trump suggested that he would not proceed with further tariffs at this time and President Xi may have indicated that China would increase its purchases of U.S. agricultural products including soybeans, corn and pork. There has also been some discussion about softening the stance on the ban in place preventing U.S. companies from doing business with Huawei, China’s largest cell phone and components manufacturer.

Following the G20 meeting U.S. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin and Trade Representative Lighthizer have been in talks with the Chinese team. Should the discussions go well, they have indicated that a trip to Beijing might follow. Needless to say, we still believe that an agreement between the Chinese and Americans is going to be a tall order and as such our expectations are that a near term resolution is doubtful. In the meantime central banks around the world have captured more of the spotlight as they have hinted at plans to ease monetary policy either by lowering interest rates or purchasing bonds, or both. We expect that investors will be more focused on monetary policy in the months ahead, looking for signals that those efforts are helping to stabilize or preferably reignite an aging bull market whose growth has been slowing for some time now.

—

We know what the U.S. wants:

- a level playing field (no government subsidies/following WTO trade rules)

- intellectual property protection

- more balanced trade (buy as much from us as we buy from you)

- improved access for American agricultural products

Is the current situation so lopsided that only the U.S. feels shortchanged? How well do we know what China is fighting for and how strong is their will to fight?

Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War and Chris Voss, former FBI international hostage negotiator, who authored Never Split the Difference would agree that having a better understanding on the perspective of your adversary creates a significant advantage. As we consider the Chinese perspective and motivations, we hope to shed some light on how the trade negotiations may go from here and why we believe the process may drag out longer than most anticipate.

Part I: The Chinese Approach to Trade Negotiations

The History that has Shaped Chinese Perspective –

Though China is much older than the U.S. (by about 3,500 years), in some ways it is much younger. What does that mean? Modern China, many would argue, was really reborn just 40 years ago after Chairman Mao Zedong’s failed attempts to ignite his country with the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution which left millions dead and the economy operating inefficiently. The Great Leap Forward was an initiative launched in the second half of the 1950’s to convert China from a primarily agrarian economy to a more industrialized and socialist style economy. This redirection of resources and mandatory collectivization of farms hurt the agricultural economy. Its state-run industry was inefficiently run and suffered significant corruption. The Cultural Revolution in its simplest form was an effort to reassert the power of the Communist party by persecuting the more independently minded population. Mao took the opportunity to arrest and or remove perceived dissidents to consolidate the power of the Communist Party which cost many lives and stunted economic growth.

China’s modern era really begins in 1978 with the rule of Deng Xiaoping who focused on balancing socialism with a free market economy. Mao’s time in leadership wasn’t a total loss however as two important things happened: (1) the struggles that China went through really paved the way and ignited people’s passion for the reforms later introduced by Deng and (2) relations with the U.S. began to thaw in the early 1970’s as efforts to end the Vietnam war led Henry Kissinger, the U.S. Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon, to make a secret visit to China. This visit eventually paved the way for Nixon himself to meet with the Chinese leadership. One important part of these discussions included the U.S. recommendation that China be admitted to the United Nations with a seat on the Security Council, instantly catapulting China as a world power. Perhaps that was just the taste they needed to rekindle the country’s desire to be a dominant power in the world, if not “the” dominant power in the world.

Most of us are familiar with what has happened since then. China became the world’s manufacturing hub as labor was cheap and plentiful. As the economy continues to develop, the Chinese are more focused on developing a consumption led economy with a desire to move up the production chain to a higher value-add role. In order to achieve this, they have placed a high importance on education and competing in technological and scientific advances on a global level. A handful of years ago an administrator at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology relayed that the Chinese had become the most published in scientific journals of any country in the world. The only problem was, they found that approximately 70% of the articles had been plagiarized! We have heard similar accounts of efforts in the manufacturing world where the Chinese have been well known to steal intellectual property, reconstruct similar products and then compete against their global joint venture partners. If we are being honest, when we are in a competitive situation where we are clearly the disadvantaged party, why would we agree to play by the rules (which, by the way, were probably drafted by the dominant player)? You probably cringe at this thought because of basic morality, but try to suspend morality for a moment and just consider it from a pure incentive standpoint—David didn’t put down his slingshot to take on Goliath with his fists.

What else do we know about the Chinese that is likely to impact the way they negotiate? The Chinese have a long history of unifying people behind an idea, even if it is a struggle. In discussing the trade negotiation process, President Xi recently referenced the Long March, a 6,000 mile march across China where Mao Zedong lead his Communist community out of the grasp of the Nationalist army, earning him respect and control of the Party. President Xi was highlighting the Chinese resolve—the ability to band together and suffer now, in order to reap the benefits for the long-term. We also know that the Chinese put up a strong fight during negotiations, but at the same time, they have a strong desire to reach an agreement where both parties can walk away looking good, maintaining their own respect. Lastly, the Chinese leadership tends to think more long-term and therefore have greater patience than their American counterparts. The U.S. leadership perspective is perhaps more short-sighted due to the relatively short election cycles where one’s fate can quickly change. Conversely, President Xi has recently taken steps to consolidate power and pave the way to remain in power for an indefinite period of time.

President Xi hints at what we might expect from the Chinese –

There are two initiatives of President Xi that can help us better understand their overarching goals which are pertinent to the trade negotiation process including the Made in China 2025 initiative and the One Belt One Road program. In addition, we can glean some valuable insight into the highest government priorities by reviewing China’s Five Year Plan.

We are in the midst of China’s thirteenth Five-Year Plan (2016-2020) which focuses on:

- Innovation: Moving up the value chain particularly in technology development

- Balancing the Economy: Bridging welfare gaps between rural and urban areas

- Greening: Developing more environmentally friendly technologies

- Opening Up: More international co-operation

- Sharing: Encouraging Chinese people to share the fruits of economic growth amongst their people

- Healthcare: Implementation of universal healthcare

Made in China 2025 is one of the policies under the Five-Year Plan

- Develop domestically the technology that will power the future (ex. Clean energy)

- Improve the quality of industrial products built in China

- Focus on converting academic research into practical application

- Invest in local Chinese companies in the following specific industries: aircraft, integrated circuits, agricultural and construction equipment, and high-end medical equipment. These are areas in which the U.S. currently has the dominant market share and are of great concern to the U.S., particularly if the Chinese government subsidizes those industries making it more difficult for U.S. companies to compete.

One Belt One Road Initiative

- China is making infrastructure investments throughout the region to open up trade routes particularly in Asia, Europe and Africa

Our Perspective on the Future of Trade Negotiations –

In summary, the Chinese plan to compete more with the U.S., not less. While the U.S. has maintained an advantage for some time in certain industries, the Chinese are targeting many of these in their Made in China 2025 initiative. It is likely that with a centralized government the Chinese will be able to more rapidly develop these industries as they can direct significant investment into those areas. There will be a lot of attention placed on the question of what “fair” is, as trade discussions evolve. The U.S., more than ever, is going to have to depend on the World Trade Organization and its European counterparts to try to keep China in check. This all comes at a time where relations with many of our traditional allies may be strained and China, through its One Belt One Road initiative, has been extending its olive branch to improve relations with many countries around the world.

If we consider what we’ve learned about the Chinese perspective and compare it to what we know about President Trump’s approach to negotiations, we can easily conclude that the process may well be drawn out over an extended period of time. While the Chinese may be looking for a “win-win” trade agreement, Mr. Trump may be looking for an “I win” trade agreement. President Xi may have time on his side as he sits comfortably in power, though he does have to keep his people happy, and a slower growing economy will be of concern. President Trump faces re-election in just over a year from now and that may lead him to want to hash out a deal sooner rather than later, although predicting his approach may not be so easy. While the U.S. may believe that China should play “fairly” (by the rules that we’ve essentially set forth, the Chinese may see it differently. We believe something will have to give in order for a sound deal to be reached.

For some further background on the U.S. perspective, and in particular the perspective of our U.S. Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, we encourage you to read the testimony he delivered to the U.S.-China Economic Security Review Commission in June 2010 entitled: Evaluating China’s role in the World Trade Organization over the Past Decade. It can be found online at the following address: https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/6.9.10Lighthizer.pdf

Part II: Current State of U.S.-China Trade

Current Situation –

After perceived progress to start the year, trade tensions have been intensifying and tariffs have resurfaced as a negotiating tactic between the U.S. and its trading partners around the world. Numerous individual goods have been targeted over the past year, including solar panels, washing machines, steel and aluminum, autos, as well as more broadly labeling industries as “national security threats” in an effort to reinforce the U.S. economy and turn up the pressure on its negotiating partners. Over the last several months, and in particular the past few weeks, sentiment has swung wildly between positive and negative as negotiations have deteriorated and the outlook for the near future appears even more uncertain. Most notably in early May discussions between the U.S. and China turned sour and progress seems to have reversed.

Source — Data from Bloomberg

Impact of a Trade War –

Direct impacts from tariffs are likely minor. Tariffs by definition are a tax on consumption. If the U.S. imposed tariffs of 25% on all $539 billion of imports the total impact would be $135 billion, roughly 0.6% of U.S. GDP. This would be a drag on GDP growth but unlikely severe enough to cause an outright recession.

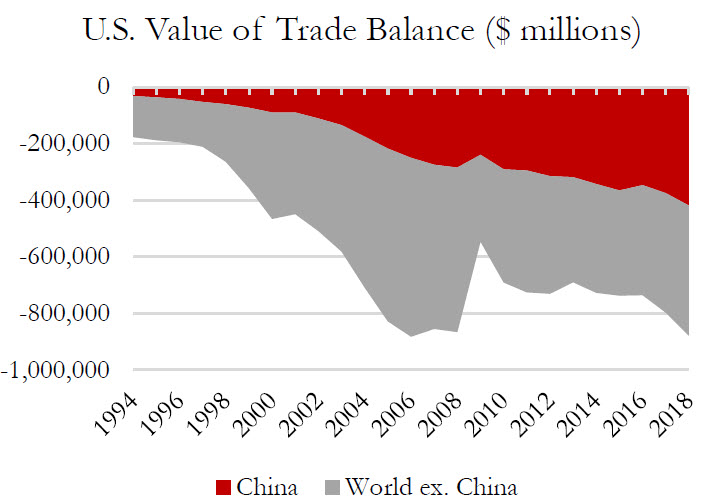

In a tit-for-tat tariff war, the scope of China’s retaliation is limited due to the large trade imbalance. China imports $156 billion of goods from the U.S. while the US imports $539 billion of goods from China – resulting in a trade deficit of $383 billion. The U.S. has a larger base of goods to slap tariffs on than the Chinese are able to retaliate with. The U.S. is a consumption driven economy and consumption spending makes up roughly 70% of U.S. GDP. The U.S. doesn’t produce enough goods to satisfy domestic demand, and therefore runs a current account deficit, importing more goods from other countries than it exports – China being the largest beneficiary.

Part of the discrepancy between trade balances has to do with China’s positioning in the global supply chain, particularly when it comes to electronics. China sits downstream within the global technology supply chain as many electronic components are imported from South Korea and other Asian nations for assembly in China, which are then turned around and exported to the U.S. and around the globe. Asian tech exports account for roughly 10% of total global trade.

The biggest impact of a trade war centers on the uncertainty it creates. With tariffs having limited direct impacts, the secondary and tertiary effects—weakened sentiment and business uncertainty—are difficult to measure or predict and pose the biggest risk. Prolonged uncertainty and extended negotiations without a trade deal will likely put a pause on business investment and consumer spending. A slowdown of spending and consumption will further weaken growth and could risk ending an already late-cycle expansion. Trade talks have raised many issues including the possibility of re-routing supply chains, blacklisting of foreign companies, restricting exports of goods such as rare earths or limiting imports of agricultural products. Beyond the threats there is also the reality that politics are likely to play an important role as we approach the U.S. 2020 Presidential election. President Trump will want to signal to his supporters that he is “winning” a trade war and has successfully negotiated a better deal with China. Meanwhile the People’s Republic will celebrate its 70th anniversary. President Xi will want to show his people that China is a tough negotiator and won’t take an unfavorable deal that puts his country in a position of weakness.

To summarize, there are many potential risks and impacts that could result from increased tensions and the above is by no means an exhaustive list. Escalation of a trade war would further disrupt bilateral ties, increase prices for consumers, and likely further weigh on global growth.

Source — Source: IMF

The Facts on Trade between China and the U.S. –

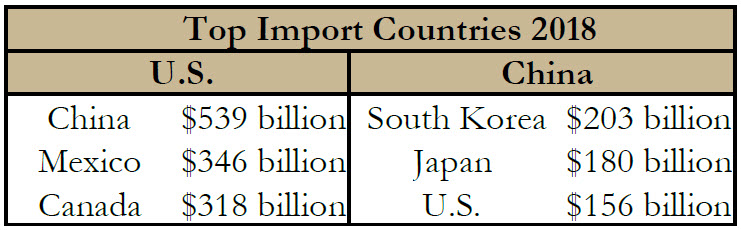

China has become the world’s factory and low-cost exports have helped fuel its rapid economic growth over the last few decades. It’s no surprise that the U.S. imports many manufactured goods from China. From a country standpoint, China is the U.S.’s largest trading partner. In 2018 total trade of goods between the two countries was roughly $696 billion. As shown in the adjacent

table, the U.S. imports far more from China than its next largest trading partner, Mexico. Meanwhile for China, the U.S. is the third largest import market, behind South Korea and Japan. China imported $156 billion of goods from the U.S. in 2018 – leading to a trade deficit of $383 billion. This trade deficit has grown steadily over the last few decades.

It’s important to note that total trade between the U.S. and the European Union (EU), at $803 billion worth of goods, is larger than trade between the U.S. and China. However the trade deficit is smaller, at -$172 billion, as imports and exports are slightly more balanced compared to the U.S.’s trade relationship with China.

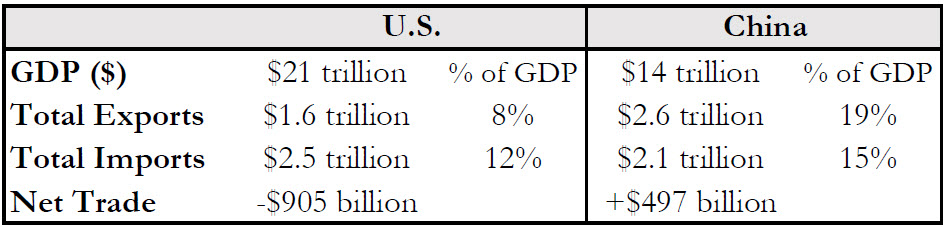

The U.S. is the world’s largest economy. China has been working to re-solidify its place as a global superpower, on par with the U.S., and will no doubt reclaim the crown of largest global economy in the not too distant future. On a nominal U.S. dollar basis per the IMF, U.S. GDP is just over $21 trillion while China’s GDP is just over $14 trillion. The Chinese economy is more dependent on trade than the U.S. Total exports of goods as a percentage of GDP are approximately 19% for China compared to only 8% for the U.S. Not only are exports more important for the Chinese economy, the U.S. is also China’s largest export market, meaning the U.S. plays a key role in China’s growth by buying Chinese goods. Over 20% of all exports from China go to the U.S. while only 9% of exports from the U.S. go to China. For the U.S., Canada and Mexico are the largest export markets.

Source — Data from Bloomberg as of 2018

Conclusion-

Taken altogether, we can expect that Chinese pride and strength will keep it from giving in to U.S. demands just for the sake of a deal. In the last forty years China has catapulted from being the ninth largest country in terms of Nominal GDP (USD terms) to second. That is nearly the size of Japan, Germany, U.K. and India combined! They have goals to be the largest economy in the World and it is doubtful those goals will be derailed. So who really holds the cards in this negotiation? Our perception is that the U.S. media (and perhaps our President) has been too simplistic in its coverage, assuming that the U.S. is in the driver’s seat and that we could force China into submission. We believe there is a path to a mutually beneficial deal, but it is likely more complicated and is likely to take longer to resolve. After the recent breakdown in negotiations there has been some hope put on the upcoming G-20 meeting in Japan in late June when Presidents Trump and Xi will likely meet in-person. Some believe a deal could be reached then. Our belief is that a deal may be more elusive. The question then will be whether further tariffs may be introduced that could put a further damper on global trade and how that impacts the investment landscape. Our recent portfolio adjustments are meant to reflect an awareness of the additional volatility this could cause, but do not make a bet significantly away from policy at this point.

Appendix: The Tariff Timeline

Recent History of Tariffs – We focus here on the dispute between the U.S. and China though there are ongoing talks between the U.S. and Europe, Japan, Mexico, and other trading partners over various concerns.

August of 2017: The Trump administration began an investigation to determine whether China’s actions related to technology transfer and intellectual property were restrictive to U.S. commerce. Under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 the U.S. Trade Representative has authority to take action to eliminate unfair practices.

March 2018: As a result of the investigation, President Trump increased tariffs on Chinese imports as a way to pressure China into negotiations to change their practices.

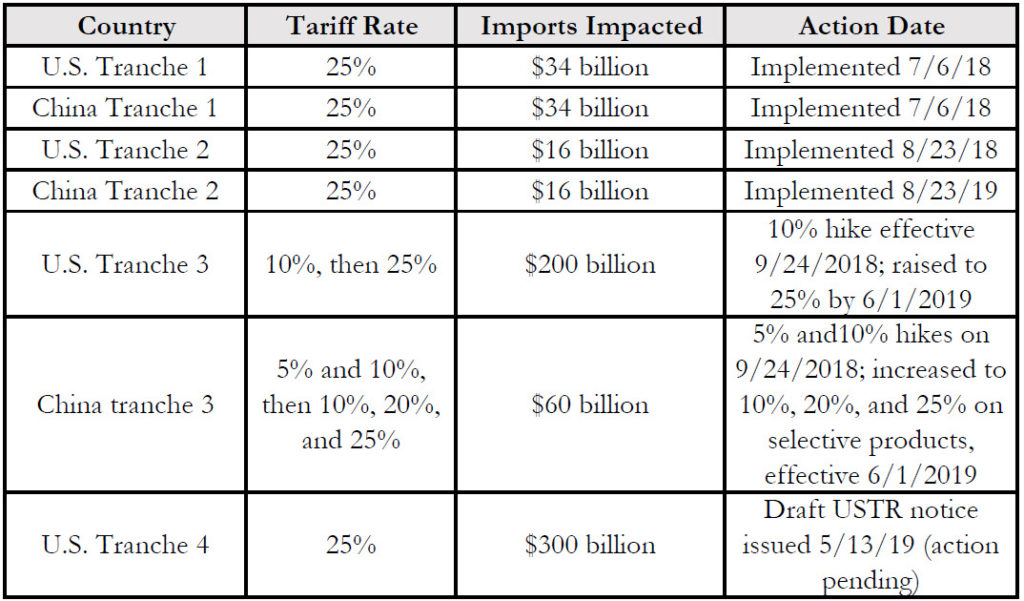

July 2018: U.S. imposes 25% tariffs on $34 billion of Chinese imports. With expectations to add another $16 billion at a later date. China retaliates with 25% tariffs on $34 billion of imports from the U.S.

August 2018: U.S. imposes 25% tariffs on $16 billion of Chinese imports. China retaliates with 25% tariffs on $16 billion of imports from the U.S.

September 2018: U.S. imposes 10% tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese imports (with plans to increase to 25% in January 2019 if no deal between the countries is reached). China retaliates with 5-10% tariffs on $60 billion of imports from the U.S.

December 2018: President Trump decided to hold off on increasing tariffs as negotiations were ongoing and news reports indicated that both sides were closing in on a deal.

May 2019: On May 5th, President Trump tweeted that negotiations had broken down and he was planning to lift tariffs from 10% to 25% on the $200 billion of goods implemented back in September. Further, indications are for 25% tariffs to be charged on the remaining imports from China that have not yet been targeted (approximately $300 billion worth of imports). Negotiations fell apart as China materially edited a 150 page draft trade agreement, reversing commitments to change laws based on the U.S. complaints around intellectual property theft and forced transfer of technology. The U.S. views these legal requirements as essential to a trade deal to ensure that current practices will change and be able to enforce reforms rather than commit to empty promises. China has retaliated by raising tariffs to 25%, starting on June 1st, on U.S. imports of the $60 billion of goods previously tariffed in September.

Source — Table from Congressional Research Service as of June 4, 2019